In January 2011 a series of protests erupted in Damascus and Aleppo, the largest cities in Syria, and quickly spread to the rest of the country. Initially in demand of democratic reforms, by April the protests were calling for the overthrow of the government led by Bashar al-Assad, whose family has ruled the single-party state since 1970. In July, the Free Syrian Army was formed by defecting officers from the Syrian Armed Forces, and a state of civil war has existed in the country ever since. Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have been killed or imprisoned on both sides, while almost three million have fled across the borders, one of the largest forced migrations since World War Two. 80,000 people are currently housed in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan alone.

Alongside the humanitarian crisis, one of the ways in which the conflict has been visible to the outside world is through its effect on the internet both inside and outside the country. In 2012, as the rebel groups were making some of their largest early advances against the government, Syria disappeared from the internet almost entirely. On the 29th of November, almost all networks within Syria became inaccessible from the outside world - and what reports did leak out suggested that mobile and landline links inside the country were down as well.

The Syrian government issued a statement accusing rebel groups of cutting the cables which brought the internet into the country - but many doubted the veracity of their account. Syria is well-served by undersea cables, all part or wholly owned outright by the Syrian Telecommunications Establishment (STE): the ALETAR cable from Egypt, ALASIA and UGARIT from Cyprus, and BERYTAR from Lebanon. It also has an overland connection to Turkey. As the connectivity provider Cloudflare noted in a blog post, the blackout would have required every connection to be cut simultaneously, which was unlikely enough, but from the network logs it was clear something else had happened: the cut-off wasn’t physical, but virtual.

A system called Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) determines how large networks interface with the internet, and beginning on the morning of the 29th, Syria’s BGP started refusing requests for connections. In effect, the routes became inaccessible because outside routers could not find a way to relay traffic in and out of the country. Over a period of a few minutes, shown in the Cloudflare video below, all connections to Syrian Telecommunications (network AS number AS29386) were taken offline, with Cloudflare claiming that "The systematic way in which routes were withdrawn suggests that this was done through updates in router configurations, not through a physical failure or cable cut." The outage lasted until December 1st, when Syria reappeared on the global internet just as suddenly.

The President of the Syrian Telecommunications Establishment, as well as of Syria itself, is Bashar al-Assad. STE is also the administrator of the .sy domain, which was first registered in 1996, through the National Agency for Network Services. Like other Syrian assets, the domain system has been extensively affected by international sanctions on Syria. In 2013, the US registrar Network Solutions seized some 700 domains which were registered to Syrian entities. The seizures were marked "OFAC Holding", indicating they were taken down under orders from the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, which administers US sanctions. Foreign companies with .sy domain names have also been targeted: the New York-based fine-art website Artsy formerly operated from art.sy and was accused of violating sanctions in the media - it subsequently switched to a .net domain, and its old location is now a (near-empty) site promoting Syrian art.

Many of the domains seized were registered to IP addresses held by the Syrian Computer Society, an organisation founded by Bassel al-Assad, Bashar’s brother, in 1989. At that time, Bashar was an army opthalmologist, but when his elder sibling was killed in a car crash in 1994 he was promoted to leader-in-waiting - and became President of SCS, which still sits at the heart of the country’s internet systems.

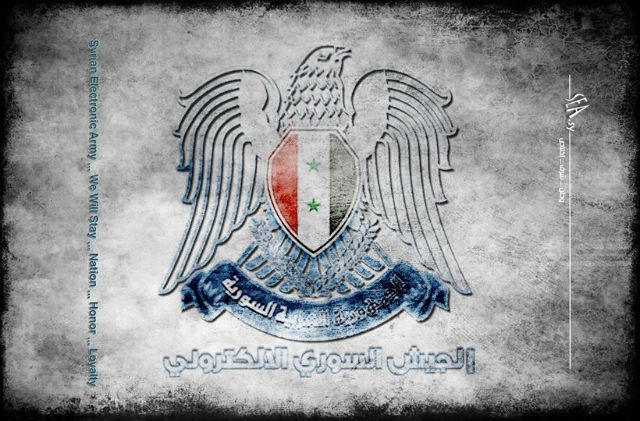

It was on SCS’s network which sea.sy first appeared: the online home of the Syrian Electronic Army. The SEA is a pro-Assad hacker group which has become notorious for hijacking “hostile” foreign news outlets, including Al Jazeera and the Washington Post, as well as opposition groups (The National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces uses a .org address; its predecessor the Syrian National Council, based in Turkey, uses .com). In April 2013 the SEA gained control of the Associated Press’ Twitter account and sent out the message "Two Explosions in the White House and Barack Obama is injured", briefly sending the Dow Jones into a nosedive and wiping $136 billion from the US stock market. While the SEA has publicly declared itself separate from the Syrian government, its claims, like those of the Syrian Telecommunications Establishment, have been widely disputed.

But the SEA may just be the public face of a far more concerted, and far more deadly, electronic campaign against Syrian dissidents. Beyond hacking into websites and Twitter accounts, the group has targeted researchers, diplomats, and journalists with contacts in the Syrian opposition in order to steal their personal details. These details may then have been passed to the Syrian government, which has "disappeared" thousands of dissidents since the uprising began.

Harvard researchers have called Syria "the first Arab country to have a public Internet Army hosted on its national networks to openly launch cyber attacks on its enemies". While some commentators have celebrated the revolutions of the Arab Spring as products of the open internet and social media activism, the legacy of these uprisings has been brutal and reactionary - and often a product, too, of those same technological developments. Repressive governments around the world remain in firm control of their local networks, and can operate across them with near impunity. The internet is real, and its connections and geographies map onto contemporary conflicts and politics. As with other domains we've explored, .sy is not just a domain name, but a window onto national and international relations and events.